Works included in this catalogue (listed in chronological order)

Buvelot Victorian scene {1904} NGV [WT]

Buvelot Summer Afternoon, Templestowe 1866 {1869} NGV [PA]

Buvelot Winter Morning, near Heidelberg 1866 {1869} NGV [PA]

Buvelot Waterpool near Coleraine (sunset) 1869 {1870} NGV [PA]

Buvelot Yarra Flats 1871 {1904} NGV [WT]

Buvelot Between Tallarook and Yea 1880 {1902} NGV [PA]

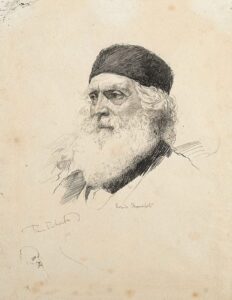

[photo: Tom Roberts: Louis Buvelot 1886 (pen and ink drawing) (Art Gallery of New South Wales; DA1-1960]

After leading a successful career in Switzerland and elsewhere (including several years in Brazil), Buvelot left his wife and travelled to Australia in 1864-5 with Caroline Beguin, a fellow artist whom he later married; she also acted as his interpreter (he always spoke French).

Later, he recalled the NGV’s 1869 purchase of his two 1866 landscapes as critical to launching his subsequent career in Australia. His style underwent a distinct development over the following decades, from subtle adjustments to his European manner towards a plein air style that hovered on the brink of Australian Impressionism. The pre-Felton Melbourne collection already clearly demonstrated this significant shift.

After his death, Buvelot was hailed by Melbourne critic James Smith as the first colonial artist to really “see” the local landscape, rather than imposing or adapting European landscape conventions. These views were echoed by the next generation of local painters, obviously strongly influenced by Buvelot’s example. McCubbin, for instance, described even the most obviously classicizing Buvelot painting in the pre-1905 collection, Summer Afternoon, Templestowe (1866), as “thoroughly Australian.” Tom Roberts (who etched a portrait of Buvelot in or shortly before 1888) was later quoted as saying that Buvelot “began the real painting of Australia,” after years in which “the memory of England prevented any appreciation of the Australian landscape.”

More recent writers, notably Tim Bonyhady, have criticized the nationalistic tenor of such remarks, while accepting Buvelot’s significance. Bonyhady observes shrewdly that pre-1945 commentators tended to fixate on “the success or failure of… artists in conveying the shape of eucalyptus trees and the sharpness of Australian light” (Images in Opposition, 1985, p.xi). However, he also notes that Buvelot awakened locals to the virtues of gum trees, and quotes Sydney Dickinson’s opinion that Between Tallarook and Yea was “probably the most important landscape that has ever been produced with an Australian subject” (Argus, 3 May 1901, quoted by Bonyhady 1985, p.121).

Refs.

For detailed biographical entries, with further references, see http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/buvelot-abram-louis-3132 (by Jocelyn Gray; first published in ADB vol.3, 1979); and Kerr Dictionary (1992), pp.121-23 (by Mary Mackay). See also Pearce Swiss Artists in Australia (1991), pp.37ff. (H.Kolenberg) and cat.13-25; AKL 15 (1997), p.395 (a detailed entry by Robert Smith, with further references); and Bénézit 3, pp.111-12 (the 4 pre-Felton paintings are the only museum examples listed)

For critical analysis of Buvelot’s significance in the development of Australian landscape painting, see in particular Tim Bonyhady, Images in Opposition (1985), esp.chs.6-7, and his The Colonial Earth (2000), pp. 159ff. (ch.6), esp.p.159 (quoting Smith’s 1888 praise of Buvelot). For the comments attributed to Roberts, as quoted by R.H.Croll (1935), see Virginia Spate, Tom Roberts, Melbourne: Lansdowne, 1972, rev.edn.1978, p.16 (with a reproduction of Roberts’ etched portrait of Buvelot on p.17). See also McDonald, Art of Australia, vol.1 (2008), pp.335ff., esp.339, and Grishin, Australian Art (2013), pp.109ff.